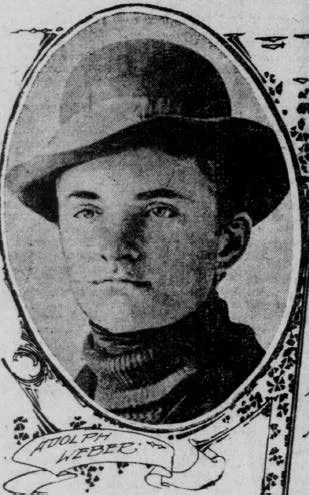

Adolph Weber - The Boy Murderer of Auburn, CA

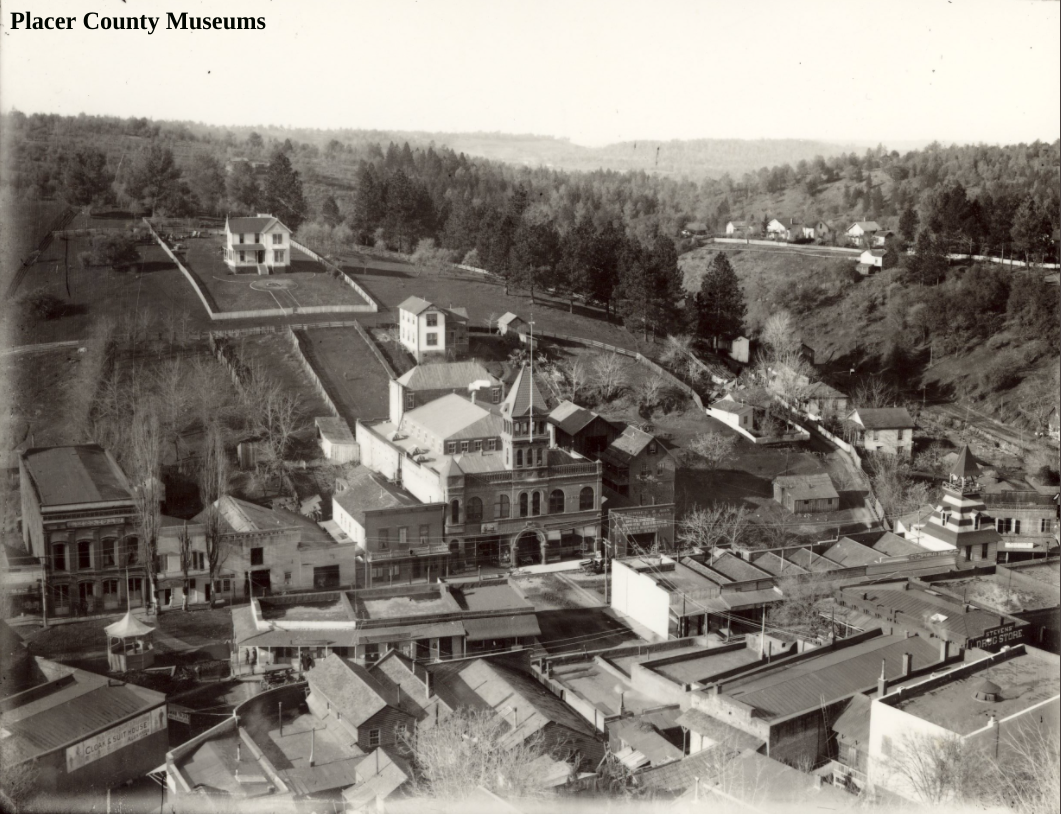

In 1904, one of the most sensational murder trials in California unfolded in the quiet foothill town of Auburn.

Four members of a respected family were dead.

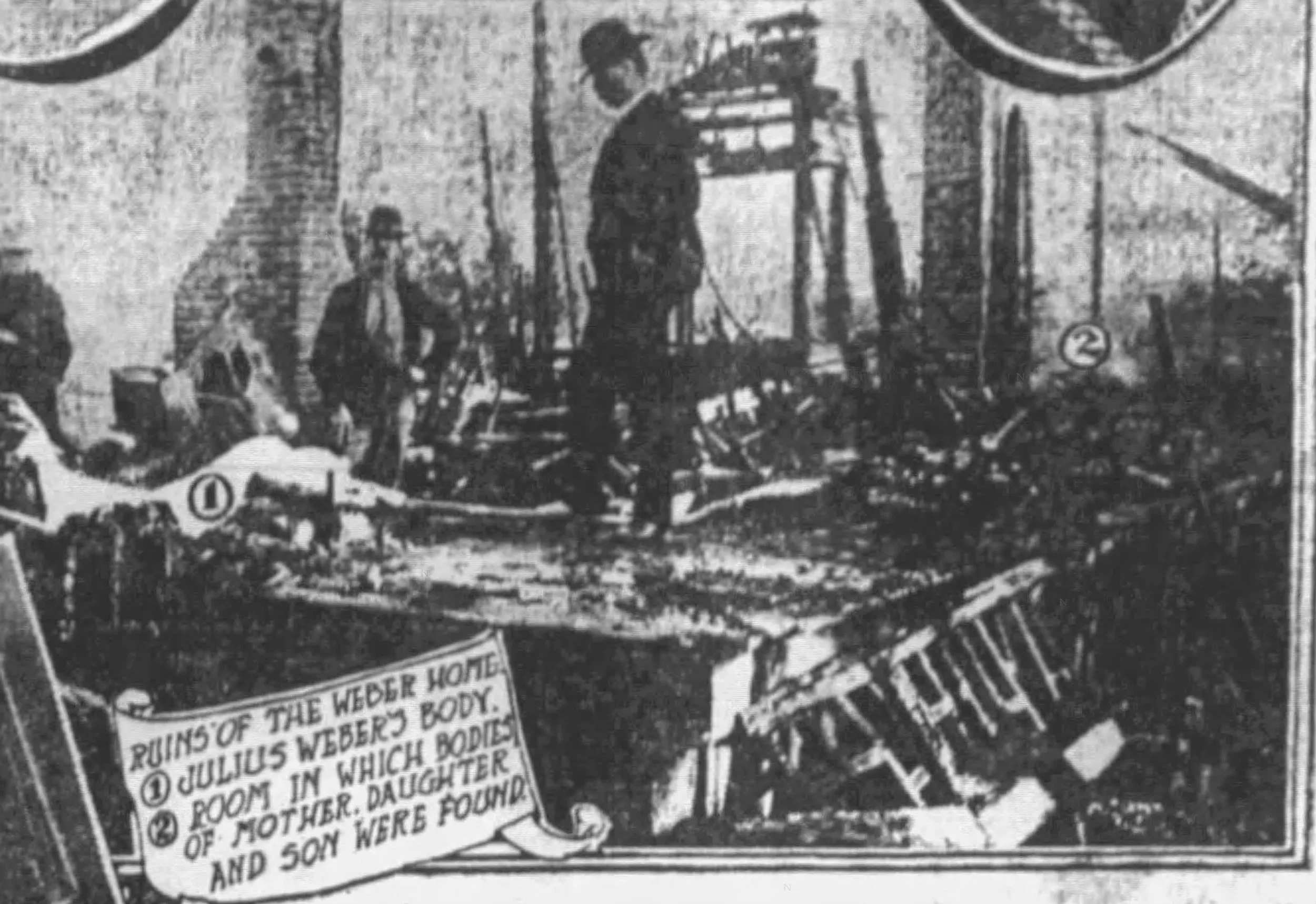

Their home had been burned to the ground.

And when it was over, California would change its inheritance laws because of it.

But the case did not begin in a courtroom.

It began inside a house.

Top left - not the white house but left of that is where this story begins.

November 10, 1904

The Weber family had just finished dinner.

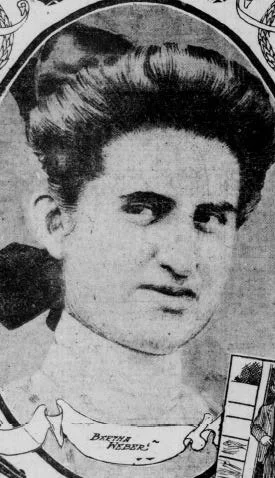

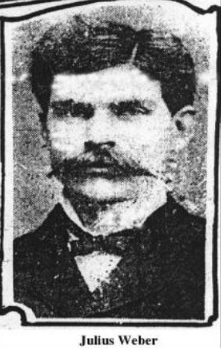

Julius Weber leaned back from the table. Mary gathered plates. Eighteen-year-old Bertha moved to the piano. Little Earl, who was disabled and rarely left his mother’s side, leaned against her shoulder.

It was an ordinary evening.

Bertha began to play a hymn.

Julius rose, tucked a newspaper under his arm, and walked down the hallway. A door closed. The piano continued.

Then a gunshot echoed through the house.

The music stopped.

Mary turned toward the hallway and hurried for the telephone.

A second shot.

Mary collapsed.

Bertha rose from the bench — stunned — and a third shot rang out. She fell beside the piano.

Earl was not shot. He was struck with the revolver itself.

Within minutes, the Weber home was silent.

Then flames began to climb the walls.

When neighbors forced entry, the house was burning. Mary and Bertha were found inside. Earl was carried out barely breathing. He died minutes later.

The following morning, Julius Weber’s body was found in the ruins. He had been shot through the heart.

Four dead.

There were no signs of forced entry. Nothing had been stolen.

The killer had already been inside the house.

And when the fire bells rang, one member of the Weber household stood outside watching it burn.

His name was Adolf Weber. He was twenty years old.

Suspicion

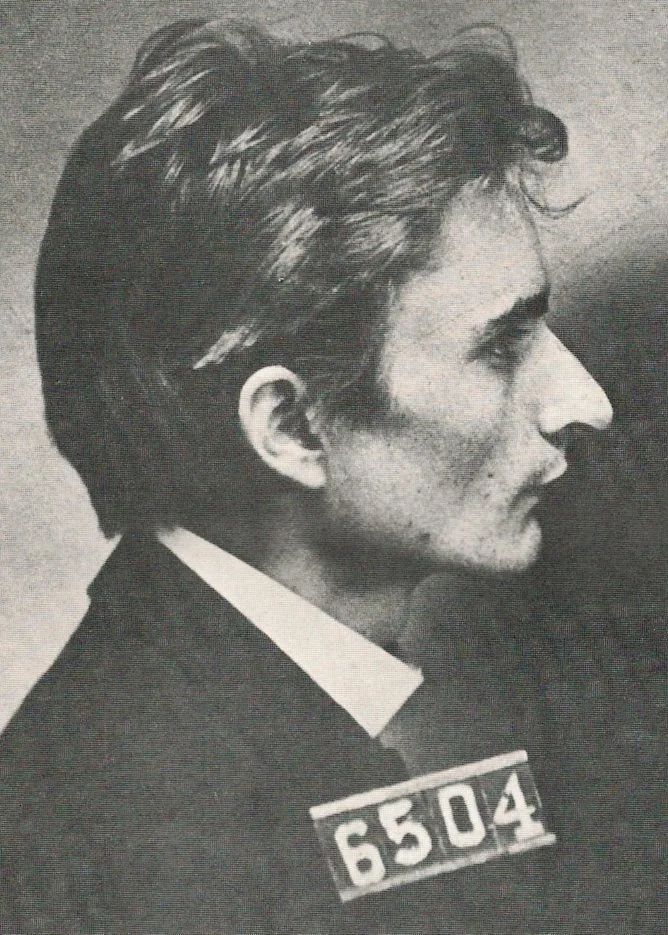

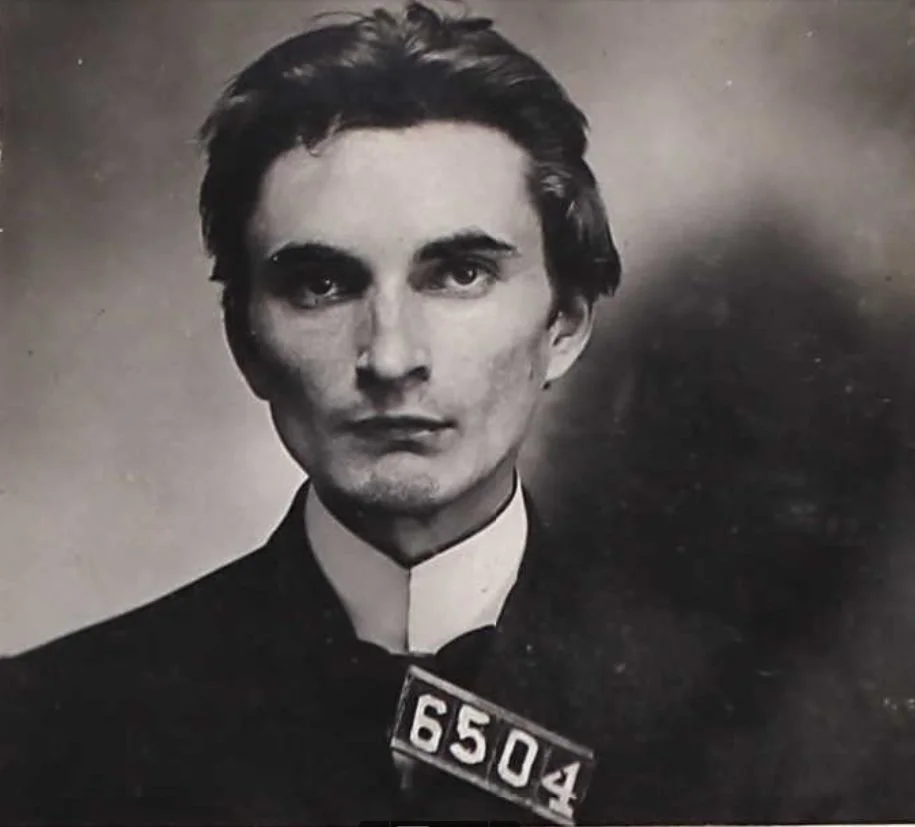

On November 12, 1904, Adolf Weber was arrested.

Autopsies confirmed the deaths were deliberate. This was not an accident. Not a tragic fire.

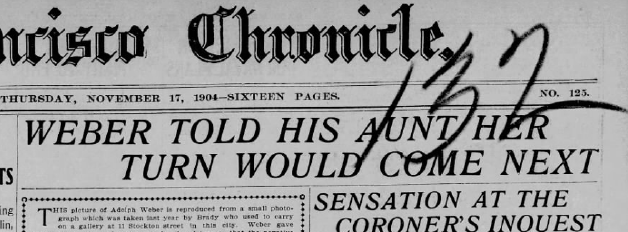

In the days following the murders, Adolf’s aunt, Mrs. Snowden — who lived next door — confronted him. She asked whether he knew more than he was saying.

His response chilled her.

“Your turn will come next.”

Whatever sympathy Auburn had extended evaporated.

Investigators began retracing Adolf’s movements that evening.

A clerk at a general store recalled that shortly before the fire, Adolf had rushed in to purchase a new pair of pants. He appeared agitated. The pants were several sizes too small. The clerk offered a better fit. Adolf refused, claiming he had ruined his previous pair by running into a fire hydrant and was late for a social engagement.

He left wearing the new pants. The old pair was rolled under his arm.

Moments later, the fire bells rang.

Witnesses later testified that Adolf broke a window and threw those old pants into the burning house.

The pants were recovered from the debris.

They were stained with blood.

The Revolver

On November 21, 1904, officers pried up floorboards in the barn behind the Weber home.

Beneath them, they found a .32 caliber revolver.

All of its chambers had been fired.

There was blood on the handle. Strands of hair were embedded in the grip.

The weapon was traced to a pawnshop in San Francisco. The store owner identified the buyer.

Adolf Weber.

The hair was later identified as belonging to Earl.

The Gold

Two days later, investigators uncovered something else.

On November 23, Coroner Shepperd and officers were digging near the barn. Under a pile of manure, they found a five-pound lard can.

Inside were twenty-dollar gold pieces totaling five thousand dollars.

It was the exact amount stolen six months earlier from the Bank of Placer County in Auburn.

On May 26, 1904, a masked man had entered the bank at noon with a revolver drawn and escaped with the money. The case had stalled.

Until the gold surfaced behind the Weber house.

When confronted, Adolf did not deny knowledge of the buried coins. Instead, he reportedly said:

“Oh, I thought you had discovered the motive for the murder. The bank robbery is a trivial matter. It’s not bothering me. It’s the other case I am thinking about. If I did take it, it was not because I needed the money, but only to see what I could do.”

Only to see what I could do.

That statement would echo through the courtroom. It suggested something beyond desperation or greed. It hinted at experimentation.

The Trial

By the winter of 1904, the case had grown beyond Auburn. Newspapers across California carried the story.

Adolf Weber went on trial for murder on January 27, 1905.

The courtroom was crowded. Reporters, neighbors, curiosity seekers.

Adolf had inherited nearly seventy thousand dollars from his father’s estate — a fortune at the time. He used it to hire one of California’s most capable defense attorneys, Ben Tabor, a one-armed lawyer known for his courtroom skill.

But the prosecution relied not on spectacle, but evidence.

The store clerk testified about the pants.

Officers described recovering them from the ashes.

Investigators detailed the revolver beneath the barn floor.

The pawnshop owner identified the sale.

The coroner described Earl’s injuries.

Mrs. Snowden repeated Adolf’s threat.

The jury deliberated for roughly twenty hours.

On February 22, 1905, they returned a verdict: guilty of murder in the first degree.

The sentence was death.

A Changing Son

Those who had known the Webers described Adolf differently just a few years earlier. He had once been considered the pride of the family. Bertha adored him. He reportedly showed patience with Earl.

But in his mid-teens, something shifted.

Accounts describe him as withdrawn, dressed in black, spending long hours alone. Rumors circulated about mistreated animals in a shed behind the property. Some claimed he raised fighting cocks and killed those that failed to perform.

Whether those stories were exaggerated or colored by hindsight is difficult to determine.

He disappeared for days at a time. Family members told neighbors he was visiting Sacramento or San Francisco. Other reports suggested brothels.

The family physician described him as a hypochondriac. There was even testimony that, as a teenager, he underwent a circumcision for what doctors of the era described as “nervous habits.”

Whether these details explain what happened is a matter of interpretation.

But in the courtroom, they formed part of the narrative: a young man who had changed.

Gradually. Noticeably.

The Gallows

Adolf appealed. There were arguments over sanity. Requests for delay.

The conviction held.

On September 27, 1906, Adolf Weber was led to the gallows at Folsom State Prison.

He was twenty-two years old.

Witnesses remarked on his composure. He walked steadily. No outburst. No visible panic.

Thirteen steps.

A black hood.

The trap opened.

The following day, the Los Angeles Times wrote that never had an assassin met death with firmer step.

The Law Changes

But the story did not end at the gallows.

Adolf had been the sole beneficiary of his father’s estate.

Lawmakers confronted an unsettling question:

Could someone murder their own parents — and still inherit from them?

The Weber case forced the issue.

California passed new legislation preventing a convicted killer from profiting from the death of a family member.

The law changed because of this case.

Two days before his execution, Adolf signed a check to his attorney for eleven thousand dollars — the remainder of his estate. The state challenged the transfer. Courts later ruled inheritance taxes were owed.

Even in death, the case continued to ripple outward.

The evidence had been simple.

Pants.

Blood.

A revolver.

Gold.

A threat.

The jury needed twenty hours.

The gallows required thirteen steps.

California needed a new law.

All because of what happened on November 10, 1904.

And it began at a dinner table.